Christopher Sinatra lives in Oswego, NY where he studies early American history at SUNY Oswego. He is working towards earning his MA in December ’15. Read Sinatra’s twice monthly blog, “Sleepwalking Through History,” on SyracuseNewTimes.com.

_________________________________

On a chilly March day in 1968, a woman walked into the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in downtown Syracuse. The magnificent Gothic Revival structure was quiet and peaceful. She thought she was alone, but soon saw a teenager standing near the altar.

Sixteen year-old Ronald Brazee had thought he too was alone, and quickly exited through the side door, leaving his coat and a metal gasoline can behind.

Outside, he asked a man if he could spare a match.

Brazee’s quick departure probably seemed strange to the woman, but then again a lot of things seemed strange in 1968. Above everything else, the American war in Vietnam had become the focal point of world-wide protest against authority of all kinds. Having formally begun in 1964, the war was, to greatly understate it, proving incredibly divisive around the world.

However, Syracuse’s place in this story had deeper roots than the 1970 Student Strike.

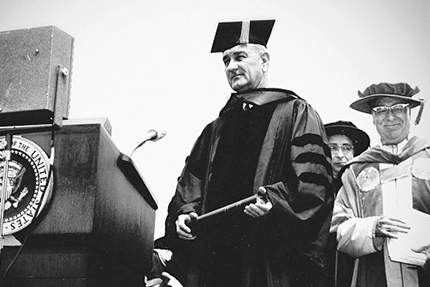

(Photo: sumagazine.syr.edu)

On August 5, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson attended the dedication of Newhouse 1 at Syracuse University and delivered the Gulf of Tonkin speech, which two days later would become the justification for expanding the conflict. However, protest was swift. David Miller, a student at Le Moyne College was one of – if not the – first to torch a draft card after Congress made the act a felony in 1965.

In Syracuse, Daniel Berrigan, who taught theology at Le Moyne, and his brother Philip, both priests, were part of the Catonsville Nine, who burned almost four hundred draft cards using homemade napalm.

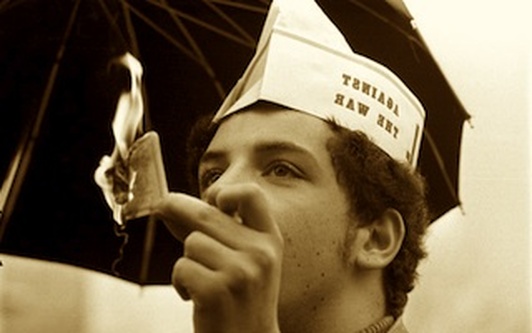

Photo: Baltimore Sun

Youth vs. their fathers, black vs. white, rich vs. poor, women vs. men and the burned vs. the unburned. There was not much to agree upon in 1968.

But one type of protest most likely made everyone uncomfortable. In 1963, Thích Quảng Đức , a South-Vietnamese Buddhist monk set himself on fire at a busy street intersection in Saigon. He self-immolated “to make a donation to the struggle” against the authoritarian Catholic leader, Ngo Dinh Diem.

The fiery image became an icon and was emulated around the world – even in the United States. Alice Hertz, Norman Morrison, Robert Chevalier, and George Winne, among others, were inspired by Quảng Đức. In 1965, a junior at West Chester State College, Patricia Ann Conway, told people she did so, “because I love God.” She insisted that she was not protesting the war, saying, “I did it because of a personal thing.”

No one can say for sure why 16-year old Ronald Brazee ran out of the Syracuse Cathedral that day and set himself on fire, dying a month later.

Photo provided by Michael Brazee.

Ron, or “Ronnie,” was the second of eight children of Hugh and Elaine Brazee. “We weren’t dirt poor, but we were barely three rungs above it,” says software engineer Michael Brazee, the fourth oldest of the siblings.

The kids, Jim, Ronnie, Greg, Mike, Jeff, Hugh (“Scott”), Michaele and Mark, resided in a small home in the City of Auburn. “We didn’t call them duplexes then, it was a half a house.” he points out.

Although Auburn was “a very Catholic town,” the Brazees was not particularly religious. “When my parents moved to Auburn, the First Baptist Church was the only group that came and welcomed them to the neighborhood, so they joined the church.” Hugh worked as a foreman for Agway and Elaine at General Products auto parts factory before staying home with the little ones while Mike was still young.

Politics did not play a huge role in the house, although it was hard, then as now, to miss the little things.

The kids didn’t have much to rebel against. For such a large family, they got along fine. “We weren’t subversives, but we were independent.”

So you were like the Brady Bunch? I asked. “No, because we couldn’t sing,” he chuckled.

“Me and Ron were really close, very tight,” Mike says. “We collected all kinds of comic books – Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, X-Men – the first issues. Stan Lee was Ron’s hero.”

The brothers also liked to go to the movies and to listen to the Rolling Stones. But Ron’s favorite band by far was Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. Ron and his cousin went to see the band when they performed at the War Memorial in February of ’68.

The boys were waiting for Elaine to pick them up when they saw someone they knew walk outside.

“Meeting Zappa after the show was probably the highlight of Ron’s life – they talked for a good 15 minutes.” Mike says that Ron penned a review in the Central High School newspaper called Of Mothers and Morality. “He was a smart, smart kid,” Mike repeated over and over. “He was very sharp, sarcastic – no, not sarcastic. He had a dry sense of humor.”

Zappa was known for his inventive style, deeply political lyrics and a strong dislike of hippies. In the song, “Who Needs the Peace Corp,” he parodied them for their perceived rose-tinted hedonism.

“I will wander around barefoot

You know I’ll have a psychedelic gleam in my eye at all times

I will love everyone

I will love the police as they kick the shit out of me on the street.”

Ron was most definitely a heavy consumer of news as well, and won third place at Central High in Time Magazine’s Current Events Contest, which consisted of, “100 questions about national and foreign affairs. Business, sports, entertainment, science, religion, literature and the arts.”

He was young, and so wasn’t as politically active as many of the college students across the country. But neither were most high-schoolers. It’s clear that Ron wasn’t living with his head in the sand. “If I could point to any direction he might have gone in, it would have been as a writer,” his brother said.

The day that Ron died, he skipped school and hitchhiked from Auburn to Syracuse with his cousin. Mike isn’t troubled that they played hooky, “It shows that he was a regular kid,” Mike says. “We used to hitchhike sometimes, it was more normal then.”

At one point the cousins split up and “sometime after 2 p.m.,” Ron walked into a gas station. The clerk refused to fill his plastic container so he returned with a proper metal gas can. He then went to the Cathedral and once inside, poured the gasoline over his body. When Catherine O’Connell entered, he fled. He quickly made his way around the building to the front of the Cathedral and asked Joseph Madden, of Solvay, for a light.

The elderly man told the Syracuse Post-Standard, “I gave him a match and he lit it and went up in flames and ran ahead.”

“Other passersby, including Charles Fahey, director of Catholic Charities, and Harry Honan, former deputy county executive, ran after the blazing youth, tore off their coats and used them to cover the flames,” the same article reported.

Photo: cathedralsyracuse.org

Fahey and James Carey, who was also present, talked to me about their memories of that day. Carey couldn’t overstate how tumultuous the times were. Fahey agreed, remarking, “It was dramatic and traumatic.” They had both seen someone who was on fire in front of the Cathedral and rushed outside. Fahey took off his coat to extinguish the flames, and says Brazee practically ran into his arms. “I was just about hyperventilating…He never lost consciousness. I almost did.”

Fahey and Carey weren’t the only people who witnessed the act. Joseph Michaels, who was driving by in a Niagara Mohawk truck called the fire department from his new radio. Tony Saya, who was standing near the Cathedral, remembered turning around and seeing someone “burst into flames…He was screaming as he ran along the street and so were the priests who ran after him.”

They all used their coats to try and put out the fire. Fahey, not knowing the boy’s religion, performed conditional last rights. Saya recalled the disturbing scene, “He rose to his feet as the ambulance came. He kind of grinned, but he didn’t say anything.”

“He doesn’t like the war. He didn’t want to go there,” Jimmy, Ronnie’s oldest brother was quoted as saying. Their father, Hugh, stated that he had no comment.

Mike says he doesn’t know exactly what drove Ron to do it. He thinks it was largely to do with his opposition to the Vietnam war, but can’t rule out mental illness either. He doesn’t think it necessarily has to be one or the other.

According to Michael Biggs, a professor of sociology (St Cross College, University of Oxford) who researches self-inflicted suffering as protest, immolation is more complicated than many think.

“Protest by self-immolation has become associated with death by fire, but the etymological root of immolation is ‘sacrifice.’” He argues that as much as it is an old phenomenon, it has made a modern comeback since Quang Duc. The ability of images of the act to be transmitted by the mass media, as well as the diminishing visibility of execution by the state are two reasons for this resurgence. Quang Duc set himself on fire in full knowledge, and hope, that people would see his death.

In Ron’s case, the assistant superintendent at Auburn gave voice to this when he told the newspaper that images of the war on television might be, “too much to take at the age of 16.”

Since the end of January, 1968, the war had reached a critical point. The Tet Offensive had had plummeted hopes that it would be over soon. In mid-February, the highest death toll of US service members in a week was reached, with 543 dead and 2,547 wounded. And on February 7, an Army Major told New York Times journalist Peter Arnett, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.”

In other words, it was no accident that the Catonsville Nine used napalm as fuel.

The draft was also a pressing issue. In the March 20th edition of the Post-Standard below the announcement of Ron’s self-immolation, a headline read, “Draft Call for May put at 44,000” and noted that this was the third continuous month with such high numbers.

As Jimmy Brazee had told the newspaper, conflating the past and present, “He doesn’t like the war. He didn’t want to go there.”

Ron had almost no chance of making it out of the hospital, as he suffered burns over 90% of his body. Not many people could visit him because of the severity of his wounds, but Msgr. Fahey thinks that local peace activist and then-priest Frank Woolever did. Mike told me that to the end, Ronnie kept his sense of humor. “He would say to my mother that when he got home he would grow a beard. Up to that point he could only grow three or four whiskers.”

Ronald Brazee died on April 27, of pneumonia. There was no public vigil after his death – only before, shortly after he was first taken to St. Joe’s. A small crowd of approximately 75 silently paid tribute.

“We will not forget Ronald Brazee – or his horror at the Vietnam war,” one sign read. Mike Brazee, recalls, “It was in the paper for a few days…for a few days…”

He is still troubled the silence which surrounded the event, both at home and in school. “There was no grief counseling for the family or his friends. We’d never even heard of it.” Contrasting this with both the changes in the news cycle and mental health treatment, he points out, “These days, we would have been hounded…. I handled it pretty well – not all of my siblings did,” Mike said.

At home, his mother would talk about it once in a while, but Hugh never would. “He was a strong man. The only time I’d seen him cry was when their grandparents came to the house after the incident.

At school, teachers didn’t seem to know how to approach the subject. Mike admitted, “It’s okay, I didn’t know what to say back.” One exception to this was an 8th grade social studies teacher, who commented on Ron’s death by saying, “well that’s a stupid thing to do.”

In an article about the Class of 1968, the headline read, “black-draped chair dominates graduation at Central High.” But this was about a board of education member, not Ron. Yet the speeches at the ceremony included plenty of politics, which calls into doubt the idea put forward by Auburn administrators that the students didn’t think about the war on an emotional level. Class valedictorian Robert Perry disapproved of opposition to the war, counting “the Vietnam war protest, crime and the Hippie movement and student revolt on campus among the wrong actions performed by the younger generation.” He asked the crowd, “if adults could trust anyone under 30.”

On the other hand, P.W. Fedorchuk, a classmate of Ron’s, wrote a poem which was published in The Citizen-Advertiser entitled “The Peace Orphan,” memorializing both his life and his cause:

A saddened day, a quiet year,

The silence does not die.

The people’s minds are mild,

His yearning soul does cry.

Reflections gathered freely,

in the sea of tranquil thought,

Questions asked so quickly,

Answers to be sought.

A burning sun, a flame of

love,

No action was in vain,

Futile words of sympathy

A sacrifice profane.

Confusion’s crowd, contained

In cold,

The hate, it makes it dim.

Alas, poor peace, thy face is

warm,

To many more like him.

More soldiers and civilians from the United States and Vietnam would die or be injured during the war. Although many young men volunteered, those who were drafted had no choice but to enter the ranks, and they were disproportionately from poor families.

If their birthday wasn’t picked they were “there but for fortune.”

While substitute teaching in a social studies classroom, I was able to see Kevin Cook teach the draft in a way I will never forget. As students told him their birthdays, he would read to them the number that had been assigned. My birthday, April 25, was number 351. I would not have won the lottery. “But,” he said, “if you were born on April 24, you would have been number 2.”

Photo: epicvietnamwarprotest.weebly.com

Ron’s mother Elaine is 92 years old and still lives independently. She is pleased that his story will be told. So is Ron’s sister Michaele, who Mike thinks probably took his death the hardest out of all of the siblings. I asked him what he thought of the idea, known then and now, as “love it or leave it.” He immediately replied that it never made sense to him. But the thing he disliked the most was when people would say everything happens for a reason.

“There are reasons that things happen, but everything doesn’t happen for a reason.”

He likened the phrase to believing that things have to happen the way they do, as if people can’t make their own choice, or act according to their conscience. “If it were true, there would be no reason for there to be trials or juries,” he said.

Finally, I asked him if his brother’s story should be more familiar to people. “There are a lot of stories, and people have to have priorities,” he said, wistfully. “But wait a minute,” he continued, his voice becoming tense, “What did Kim Kardashian wear last night? When I was working with my dad and held the flashlight in the wrong direction he would say, ‘It ain’t help if you ain’t helping.”

Regarding Ron’s death, he had a similar thought. “The story can’t be told if it can’t be told….If Ron were alive he probably would have been there with the students at Kent State.”

What a tragically ironic thought.