Composer Cliff Martinez creates atmosphere: waves of sound (or silence) that envelop characters, scenes and plot lines. Aural actors composed of synths, strings and digitized inflections. And, as of late, he’s also created quite a buzz within the film industry.

Traffic, The Lincoln Lawyer, Contagion and Spring Breakers are just a few of the flicks that fill Martinez’s diverse résumé. Martinez, 59, has been working since the late 1980s, starting with his first score for Steven Soderbergh’s landmark indie feature Sex, Lies, and Videotape. He has gained more acclaim among critics and filmgoers, thanks to his music for the 2011 Ryan Gosling car caper Drive, directed by Danish filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn.

Drive’s soundtrack CD on Lakeshore Records reached No. 31 on the Billboard Top 200 chart. Its sparse, melancholic synth-pop sound, a style that matched the film’s 1980s aesthetic, drew out the moody John Hughes-ian misfit inside us all.

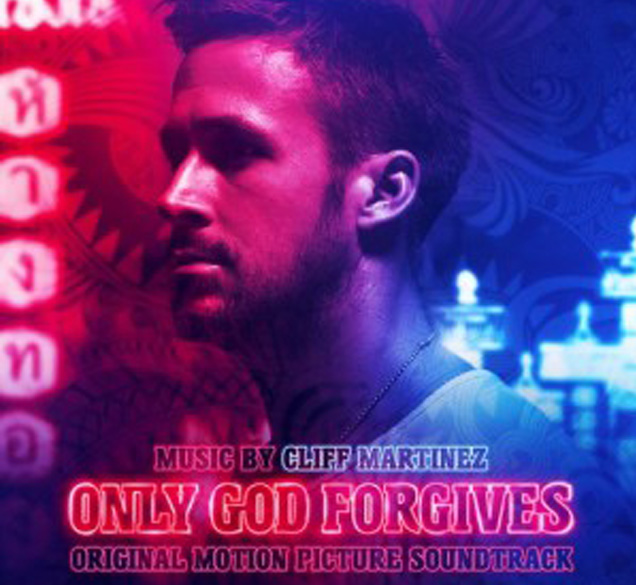

Martinez also composed the score for Refn’s controversial crime drama Only God Forgives.

You began your music career drumming in bands like The Weirdos, Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band, and, most notably, the Red Hot Chili Peppers. What ultimately got you interested in film scoring and, in turn, made you switch paths creatively?

It started with the transformation of music technology, which was just beginning to take off in the late 1980s. Andy Gill, who produced the first Chili Peppers album, introduced me to the Linn drum machine. I was kind of fascinated by it but at the same time a little fearful of it: I could tell that drummers would be a vanishing species. I was amazed by its capabilities and the potential.

At that time some affordable, primitive music samplers and sequencers were on the market and that’s where it started. I bought an MSQ-700, the first Roland sequencer, the S2000 sampler, and SP-12 drum machine.

I was amazed by all this technology but I couldn’t figure out an application for it. I was with the Red Hot Chili Peppers at the time and it really didn’t seem appropriate for anything they were doing so I just started writing music, something I hadn’t done much of. I’d always made contributions to the bands I was in—arrangements and stuff—but I didn’t consider myself a composer until all of these new gadgets became available and I was able to produce some strange music. But, again, I didn’t know where to put it.

One day I was channel surfing and I saw an episode of Pee-Wee’s Playhouse. I thought, “Ah, I can make music like that.” Fortunately, one of the show’s directors, Stephen Johnson, was a friend of the Chili Peppers. I approached him and got my first job writing music for Pee-Wee’s Playhouse. I was enamored by the whole process of putting music to picture.

Do you adhere to a specific creative process?

Usually, I’m hired when there’s a picture to look at but that’s not always the case; sometimes there’s just a script. I look at the picture, get the director’s thoughts, and then wait around for lightning to strike.

What’s usually the catalyst for those lightning strikes?

When I’m brought in, they’ve been editing for a few weeks and there’s usually something in {the film} called temporary music. A lot of composers really dislike it because they feel like it biases the process in favor of pre-existing music.

But that’s there and it gives you a lot of information. It reveals the director’s preference and tells you things about placement. The music usually comes out of nowhere but that temporary music is a good rough guide to start with.

You’ve done scores for Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive and Only God Forgives. How did you guys meet?

Brian McNelis, head of Lakeshore Records, was filming me at my house; we were doing a promo for The Lincoln Lawyer. I was playing the cristal baschet, kind of a unique experimental instrument {involving oscillating glass cylinders}. He was friends with Adam Siegel, who was one of the producers for Drive, and Adam had asked Brian if he had any suggestions for a composer. Brian recommended me.

The next thing I knew Nicolas was over at my house. He’d seen this promo where I was playing the cristal baschet so he came over and I played it for him in person. We hit it off immediately and he liked my résumé. Shortly after that, he showed me the film and I was hired. And then he went back to Copenhagen and we never saw each other again— except through Skype.

What is your working relationship like with Refn?

He’s as hands-on as he can be when you consider that he’s based in Copenhagen and I’m in Los Angeles. We talked daily over Skype; we talked about specific scenes and the dramatic function of the music. Though we’re not even in the same country, I’d say we’re quite close, creatively.

What about Refn’s work appeals to you?

Well, I guess the thing I always asked myself when working for somebody is, “What’s in it for me?” What was in it for me was that Nicolas, though he liked my past work, wanted something fresh and different. He doesn’t want to reference his past work and he demands the same thing of the music. That’s the big attraction.

With Drive, I saw the movie. Usually I get a rough cut but Drive was a locked picture, a final cut except for the sound and the music. I just really loved that film: That’s why I was excited to work with him. That film was just great.

What drew you to Only God Forgives?

Well, I did that because Nicolas didn’t want to repeat himself. Rule No. 1 was “Thou shalt not sound like Drive.” Oftentimes people come to me because they like something I’ve done in the past and Nicolas said, “I don’t want to hear anything you’ve done in the past. I want something different.” That was the lure.

The soundtrack to Drive was hugely popular. Why do you think so many people got into that recording?

It’s still kind of mysterious to me and I think Nicolas would probably scratch his head, too. Most of the songs {the soundtrack includes recordings by electronic artists including Johnny Jewel, College and Kavinsky} have been around for a while, so I don’t know. There was just a magic combination of elements that made Drive a special film and I generally think that people go after the soundtrack because they want a souvenir. And with Nicolas’ films, both Drive and Only God Forgives, the dialogue is so sparse; that gives the music a particular emphasis. Plus, Nicolas is very music-centric. I hadn’t written any pieces of nine-minute music for a film until I started working with Nicolas. He places a great deal of importance in the score.

Did Nicolas’ need for longer pieces free you creatively or did that need make writing a challenge?

The importance of the music was a challenge but it was a welcome challenge. Spring Breakers was similar because it was wall-to-wall music. I did, like, 50 minutes of music, Skrillex did a lot of music, and then there were a lot of songs. I like when the music is given a starring role.

With Only God Forgives, were there any specific musical elements you tried to incorporate? The film takes place in Bangkok so I imagine that was an important factor.

Yeah, I wanted to incorporate Thai musical culture into the score. I thought part of what was interesting about the film was the setting. The first thing I had to do was create the karaoke tracks for the on-screen singing; the film had to be shot to those songs. It got a little diluted with all of the other influences that came into play but originally I wanted a very strong Thai flavor.

I read somewhere that Refn wanted to incorporate some John Carpenter-style horror music into the film. Where does that come through exactly?

I think I only got that reference once.

There’s a bonus track on the soundtrack called “Time to Meet the Devil.” There’s this line of dialogue where Tom Burke, who plays Billy, says, “Time to meet the devil.” And then the Chang character {played by Vithaya Pansringarm} is introduced. With that moment, Nicolas asked me to give him something along the lines of Halloween. At that point though, all of the music had been recorded and that particular track didn’t fit. It’s a cool bonus track, though.