(SPOILER ALERT for HBO’s The Leftovers seasons one and two.)

Usually, when we talk about music that accompanies scripted entertainment, we call it “film music.” But music can have a profound effect on how we perceive any visual medium, including TV. As TV has become more sophisticated — mirroring film in quality and prestige — its musical scores have also evolved.

Film music — or “programmatic music,” as it’s called among composers — colors our emotions about the characters and their situations, and sets the stage for what will come next. When the music is ominous, we know something scary or violent is coming. When the music is sad, it helps us understand how the characters are feeling. When the music is happy, it amplifies the humor or joy of the scene. It can also have a confounding effect when what we hear does not align with what is happening on screen. This too can color our view and add depth.

Last year, the pilot episode of HBO’s The Leftovers began with a woman putting her screaming infant into her car. When she gets into the front seat, suddenly, he stops crying. She turns to look, and he is gone. Poof. At first, she is confused. Then, she begins to panic. A young boy is standing by an empty shopping cart asking where his dad went. A driverless car crashes into another in the street behind her. She begins to scream, as a soft piano agitates with even arpeggios beneath her voice. Her pain is apparent, but the music is not explicitly sad. Nor is it as jarring as the situation it underscores. Two percent of the world’s population has vanished. The music is pressing and mysterious, just as the show has been.

So far, the second season of The Leftovers has been nothing short of spectacular. Three episodes into a 10-episode season, the show and its characters have begun to lift the edges of its notoriously heavy cloak of grief. Underneath, there looks to be life and nuance. The protagonists have moved from fictional Mapleton, New York, where they lost nearly everything, to the small — also fictional — town of Jarden, Texas, a town recently renamed, “Miracle.” There, in a mystical place where no one was taken during the rapture-like, “Sudden Departure,” they have some room to breathe and dust off the neglected tools in their emotional stable.

Part of what was so frustrating about the first season was its persistent desolation. Characters were never anything warmer than melancholy, and nothing but bad things happened to them at a constant rate. This grinding sadness was intensified by a hauntingly beautiful original score by the German post-minimalist composer Max Richter. In Richter’s theme, the oscillation between major and minor with a slowly lilting piano line above captures the sorrowful mood of the show, leading the ear from loss to hope, back to a loss, over and over.

There is a hollowness to Richter’s minimalist style. With a few repetitive notes and themes, he perfectly captures what you imagine one might feel if their loved one was in front of them one moment, and then suddenly gone. It freezes that moment between pleasure and pain; normality and disorder; and stretches it out, opening up the characters’ grief and spreading its contents across the soundscape. The brilliant music and the unrelenting sadness made the show almost unbearable to watch.

This season, in what might be a response to a great deal of criticism of the show’s relentlessness, each episode begins with a disconcertingly happy tune about death and the afterlife. “Let the Mystery Be” was recorded in 1992 by Iris DeMent, a talented singer-songwriter who, fittingly, discovered music through the gospel of her Pentecostal upbringing, and has largely floated under the mainstream radar throughout her nearly 30-year-long career. She had her moment in the mid-1990s, when another famous TV show Northern Exposure featured her song, “Our Town” in the series finale. DeMent recently released her sixth studio album, a collection of works inspired by Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

“Let the Mystery Be” may be the perfect new theme for The Leftovers‘ second season. It’s about accepting that we can’t know what will happen to us when we die.

“Everybody’s wonderin’ what and where

They all came from

Everybody’s worryin’ ’bout where they’re gonna go

When the whole thing’s done

But no one knows for certain and so it’s all the same to me

I think I’ll just let the mystery be”

For those left behind after the Sudden Departure, acceptance is a key tension this season. While the first season was relatively sparse in its use of music outside Richter’s score, in season two, there has been a noticeable turn to music to set the tone and call out the friction between appearances and reality.

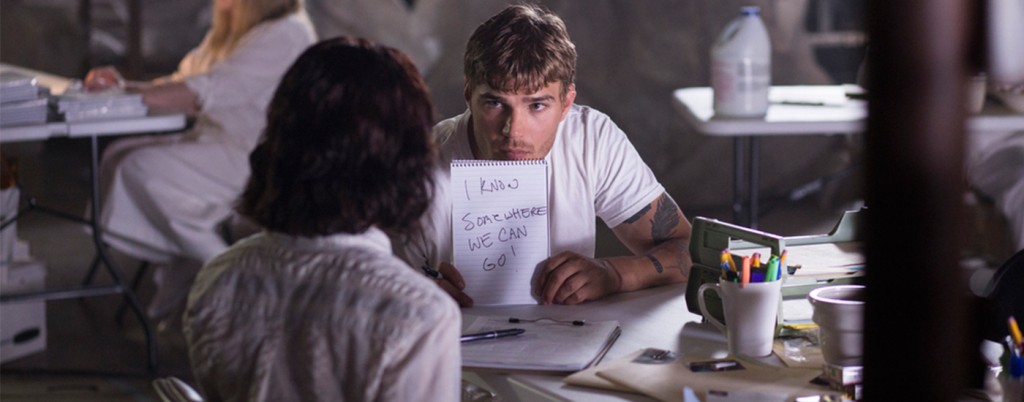

On the surface, everyone seems to be moving on. “Let the Mystery Be” is a cheerful, forward-facing, infectious folk tune to which you can’t help but nod your head or tap your toe, as you watch the characters embrace lightness and go forth to live their lives. Kevin and Nora have started a family together and moved across the country for a fresh start. Tommy has returned to the “real world” from his jaunt in the company of Holy Wayne — or so we thought, until this week. Laurie has emerged on the other side of her brief membership in the cult of the Guilty Remnant, returned to her life’s work and begun helping others.

And yet.

Kevin still struggles, privately, with his demons — namely, the ghost of G.R. leader, Patti. She haunts and taunts him. He tries to avoid her through loud music, blaring angry tunes like the Pixies,’ “Where Is My Mind” and, “Brave Drum” by The Catheters. Finally, when he refuses to acknowledge her, she physically assaults him. He, like his father, can no longer drown out the people no one else sees.

Nora’s pain exploded out of her last season, when the G.R. put life-sized replicas of her departed family members in her dining room. She is now pressing forward, holding on to the hope offered by the Departure-free town of Miracle with fists like vices. The sweeping, “Take It All” by Ruelle codifies her epic expectations: Through hell’s gate / The ground shakes / And valor wakes / And so it begins.

Laurie’s musical arc in the third episode may be the most interesting. There is no lyricism to her inner score. Her world is punctuated by a harsh and driving drum kit solo. It is, frankly, deafening and deadening to the emotions. When she is with others, Richter’s score connects her to the tragedy. And when the story of her journey from doting mom to the other side of cult membership is thrown back at her, and she is brought face-to-face with her sins, a smooth soundscape spreads beneath her. The percussiveness of her loneliness is replaced by a rising heartbeat-like pulse.

Indeed, Richter’s score still has a place in this new, more nuanced world. Coupled with the other, cleverly selected music and the welcome injection of some semblance of hope — even if it is still rejected more often than not — the patient themes of The Leftovers’ first season are as poignant as ever. As long as grief isn’t the only emotion that the music underscores, the characters — and we, the audience, with them — can let the heavy sadness slide into the past, and move forward to find out what’s next. How does one move on from such grief? Is it possible?

And so it begins.