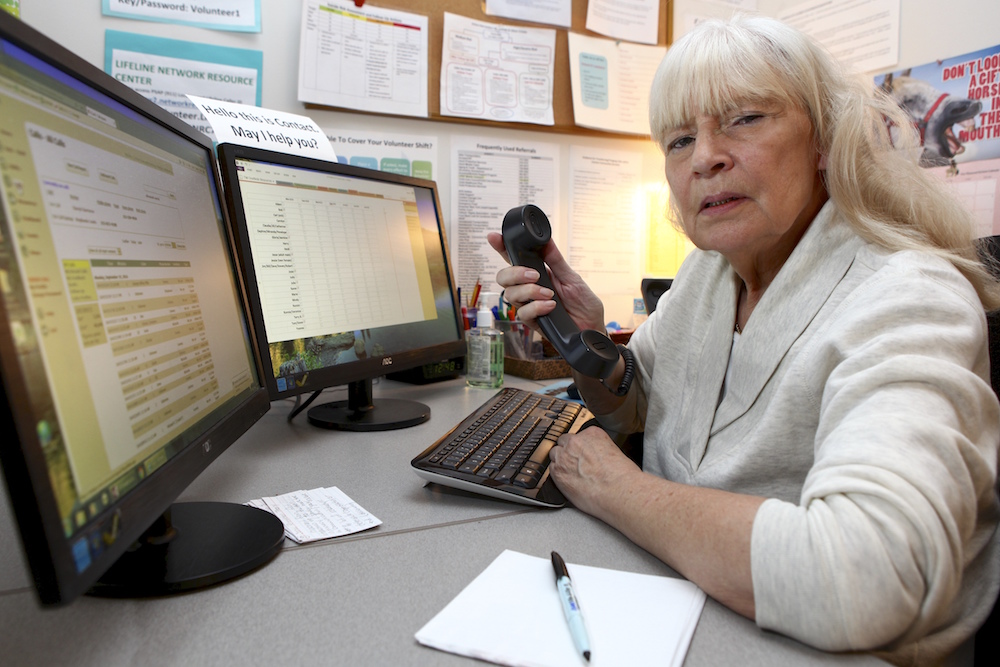

When Sue Navagh answers the Contact Community Services’ telephone hotline, she’s prepared to listen with empathy. She knows that the person on the other end of the phone could be enduring fear, pain and panic that might lead her to consider ending her life. She’s been there herself.

About 10 years ago, Navagh’s husband of 26 years left her suddenly. They had just dropped the youngest of their three sons off at college, and Navagh hadn’t seen it coming.

“It was completely unexpected,” she said last week during a break from her volunteer shift at Contact. “I was in love and ready for our next adventure.”

Suddenly, she was single, living in an empty nest and had no idea what to do next. She worried about money, especially paying for health insurance. Then her beloved dog, Jake, died, and her life seemed increasingly out of control.

“I was feeling desperate,” she remembered. “I thought my life was going to be over. My life looked like a black hole. The boys were gone. The wonderful retirement life we had planned was gone. It was like, ‘Do I really want to bother?’”

An acquaintance suggested Navagh call Contact. She did, and the calls helped her regain her footing. Now “happily single” and retired, she volunteers for Contact’s crisis and suicide prevention hotline.

Over about two years, she called Contact “a couple times a week to hear a kind word.”

“These people got me through some very difficult nights,” she said. “It took me a long time to get out of the fog. Without them, I probably wouldn’t be here.”

Navagh, a Contact hotline volunteer for about two years, shared her story during September’s National Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, a time to promote resources and discussions about suicide prevention. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers suicide a serious public health problem. It is the 10th leading cause of death for Americans.

In 2014, more than 42,000 Americans took their own lives and almost half a million Americans received medical care for self-inflicted injuries, according to the CDC. More than 1 million adults self-reported a suicide attempt, and 9.4 million adults self-reported serious thoughts of suicide.

The U.S. suicide rate in 2014 was the highest since 1986, the National Center for Health Statistics reported in April. Researchers found increases in every age group except older adults, with a particularly steep increase among women. After years of nearly consistent decline, suicide rates have increased almost steadily from 1999 through 2014, according to the agency. In 1999, 29,199 died from suicide.

It’s unclear what caused the increase in suicide rates, but researchers note “the plight of less-educated whites, showing surges in deaths from drug overdoses, suicides, liver disease and alcohol poisoning, particularly among those with a high school education or less,” The New York Times reported in April. Researchers said the analysis “painted a picture of desperation for many in American society,” The Times wrote.

Suicidal thoughts often emerge around a loss — of a pet, a relationship, a loved one or a job, said Cheryl Giarrusso, director of Contact’s Crisis Intervention Services. She oversees the agency’s 24-hour hotline, Crisis Chat and 211 resource line. Contact also is a backup call center for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

“What’s a crisis for one person might not be a crisis for you,” she explained. “If we really open our eyes, we know someone who’s struggling.”

Giarrusso’s goal for Suicide Prevention Awareness Month is to remove the stigma that prevents people from telling their story about suicidal thoughts. “If you allow a person the room to talk about why they don’t want to live, that creates room for them to talk about why they want to live,” she said.

Although national experts are puzzled about what’s behind the increase in suicide rates, Giarrusso pointed to the divisive political climate.

“We are barraged by so much negative news,” she said. “We know about so much horrific stuff happening. How can that not affect people who are not as resilient? Seeing a little boy’s body wash up on shore or that little boy’s face in Allepo — how can that not affect our well-being?”

Nine full-time, 20 part-time and 50 volunteer counselors staff Contact’s phones 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Volunteer training includes 45 to 50 hours, and staff undergo even more training. (To learn about volunteering for Contact’s hotline, call 251-1400.)

Anthony Steele, who works 30 hours a week on Contact’s phones, said people are in denial about suicide. He hopes that the issue comes out of the closet, as LGBTQ issues have in recent years.

“There are a lot of myths about it,” he said. “We just need to be open about it.”

Among the misconceptions Steele rebuts: People really want to kill themselves; people who are suicidal can’t be helped; and depression and suicide are always linked.

After four years, he’s “pretty good at talking to people in a calm, respectful way” and aims not to “add to the chaotic situation” when people call in crisis.

As a person in recovery himself, Steele can empathize with callers struggling with substance abuse problems. He’s also increasingly conscious of connections between homelessness, mental illness and substance abuse.

“People don’t need to be judged,” he said. “They just need to be helped.” People in pain, he added, “are not attention-seeking. They’re attention-needing.”

He’s heard a lot of people worried about finances and lack of jobs. “A lot of people just want to talk about their suicidal feelings,” he said. “They vent. We talk for 15 minutes and they’re fine.”

Calls like that made a difference in Navagh’s life. Contact counselors helped her; now she wants to return the favor to people who are feeling desperate.

“I tell people, ‘You have people who are here for you,’” she said. “I tell them, ‘Give it time. You deserve to be happy. If you’re not, call us. We’re on your side.’”[snt]

Renée K. Gadoua is a freelance writer and editor. Follow her on Twitter @ReneeKGadoua.

Suicide Warning Signs

- Talking about wanting to die or kill oneself

- Looking for a way to kill oneself

- Talking about feeling trapped or being a burden to others

- Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs

- Acting anxious or agitated; displaying extreme mood swings

- Sleeping too little/too much

- Withdrawing/isolating oneself

- Showing recklessness or rage

- Source: Contact’s Crisis Intervention Services

How To Get Help

- Contact 24-hour Hotline: 251-0600

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: (800) 273-TALK (8255)

- Online Crisis Chat 24/7: suicidepreventionlifeline.org

- Contact’s Crisis Chat: Contactsyracuse.org (See website for hours.)

- To learn about volunteering for Contact’s hotline: 251-1400

- Central New York Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention:

- afsp.org/chapter/afsp-central-new-york; 664-0346

Out of the Darkness

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention researches, creates educational programs, advocates for public policy, and supports survivors of suicide loss. The AFSP holds its local Out of the Darkness walk on Saturday, Oct. 8, noon to 2 p.m., at Long Branch Park (Westshore Trail).