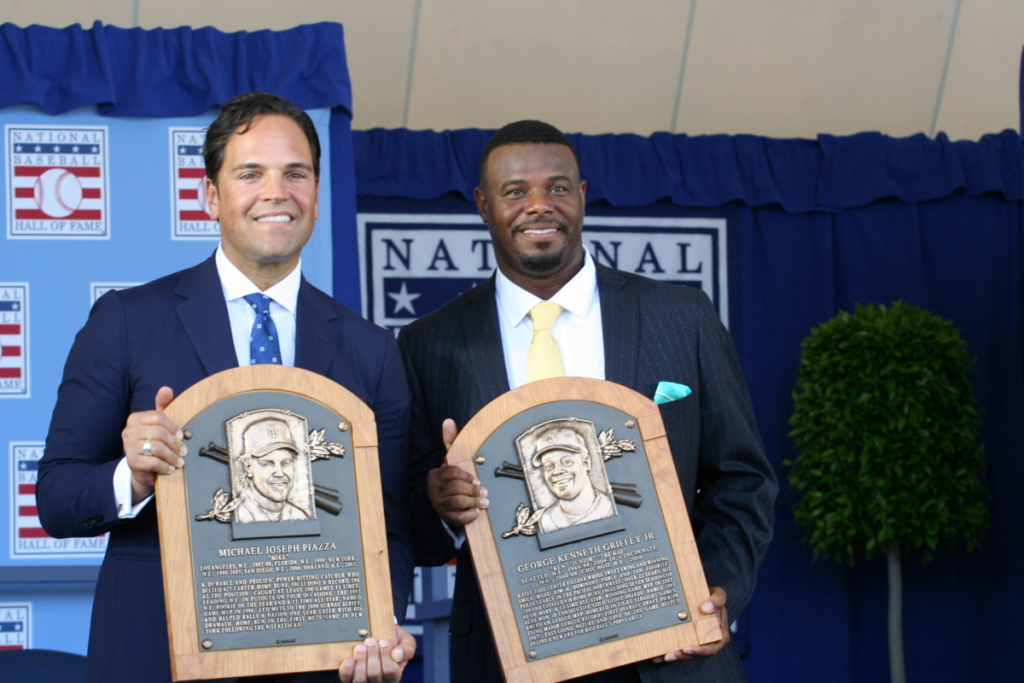

The National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Class of 2016 featured two players who started their careers on the opposite ends of the baseball food chain.

Ken Griffey Jr., the son of a star major-league outfielder, was born with one of the sweetest left-handed swings in baseball history and became the first No. 1 overall draft pick to be elected to the Hall of Fame. Drafted out of high school in 1987, he made his major-league debut with the Seattle Mariners at age 19 in 1989 and within a few years was the game’s best all-around player.

Mike Piazza, the son of a successful car dealer, was selected by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 62nd round of the 1988 draft — the 1,390th player picked — and only because Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda was a close friend of Piazza’s father, Vince. Piazza kicked around the minor leagues for five years and nearly quit in 1990 because he was sitting on the bench for the Dodgers’ Class A team.

But in the end, a player who always had to prove people right (Griffey) and a player who always had to prove people wrong (Piazza) ended up in the same place on induction day in Cooperstown. And to hear their speeches on July 24 before 50,000 people at the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, the common denominator was that despite their starting positions, both players needed plenty of help to reach the finish line.

“One of the most amazing things about the Hall of Fame is that no one goes in here alone,” Piazza said. “We all have had many people helping us, inspiring us, coaching us and, yes, sometimes kicking us in the rear.”

Piazza, who spent the bulk of his 16-year career with the Dodgers (1992-1998) and New York Mets (1998-2005), is considered perhaps the greatest hitting catcher of all time, with 427 career home runs (397 as a catcher) and 1,335 RBIs. The 1993 National League Rookie of the Year and a 12-time all-star, Piazza is receiving more credit for his defense now than he did during his career because of the modern emphasis on calling games and “framing” pitches (moving the catcher’s mitt subtly to make balls look like strikes).

On Sept. 21, 2001, in the first game at Shea Stadium since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Piazza hit one of the most dramatic home runs in baseball history as his eighth-inning blast lifted the Mets to a 3-2 win over the Braves. Many say that Piazza’s home run started the city’s healing process on an emotional, tear-filled night when the players and fans honored New York City firefighters and police.

“The true praise belongs to police, firefighters, first responders, who knew that they were going to die, but went forward anyway,” Piazza said. “I pray we never forget their sacrifice and work to always defeat such evil.”

In his 28-minute speech, Piazza thanked his fans and several of his managers, coaches, teammates and family members who enabled him to rise above his 62nd-round status. Among his notable champions was Lasorda, a Hall of Fame manager who convinced the Dodgers to draft Piazza, always encouraged him through his minor-league struggles, and then traded veteran catcher Mike Scioscia to make room for Piazza in Los Angeles.

Piazza also singled out Reggie Smith, a former Dodgers minor-league instructor who, when he heard Piazza had quit, went to Piazza’s home and told him to get back to work and do what the Dodgers told him to do.

“There are a handful of people in your life who change the direction of your destiny. Reggie was this for me,” Piazza said. Then, looking at Smith in the crowd, he added, “You are a great hitting coach, but the biggest lesson that you taught me was how to get through the game of life and to never quit.”

And Piazza, fighting back tears, thanked his father, who suffered a major stroke a few years ago but was able to attend the ceremony. Piazza said his father always dreamed of playing in the major leagues but couldn’t follow that dream as he needed to support his family.

“My father’s faith in me, often greater than my own, is the single most important factor of me being inducted into this Hall of Fame,” said Piazza, who was elected in his fourth year on the ballot. “We made it, Dad. The race is over. Now it’s time to smell the roses.”

Griffey’s relationship with his father was developed in major league clubhouses, as Ken Griffey Sr. reached the major leagues soon after Junior was born and played 19 years, including the last two with his son in Seattle. Griffey Jr. has said that his favorite moment in baseball occurred in 1990, when he and his father hit back-to-back home runs for the Mariners.

“My dad taught me how to play this game, but more importantly he taught me how to be a man. How to work hard, how to look at yourself in the mirror each and every day, and not to worry about what other people are doing,” Griffey said.

“See, baseball didn’t come easy for him. He was the 29th-round pick and had to choose between football and baseball,” Griffey continued. “And where he’s from in Donora, Pa., football is king. But I was born five months after his senior year and he made a decision to play baseball to provide for his family, because that’s what men do. And I love you for that.”

Dubbed “The Natural” and “Kid,” Griffey was a 13-time all-star and 10-time Gold Glove Award winner who ranks sixth on baseball’s all-time home run list with 630. In the 1995 American League Division Series, Griffey put an exclamation point on his greatness with a record-tying five home runs in the five-game series against the New York Yankees and he famously raced home from first to score the winning run in the 11th inning of the fifth and final game of that series.

But Griffey — who, in his first year on the Hall of Fame ballot, received 99.3 percent of the vote, the highest plurality in the history of the election that started in 1936 — made it a point to say that he needed the support of his managers, coaches, teammates and family members to become an all-time great.

“The two misconceptions of me are that I didn’t work hard, and that I made it look easy,” Griffey said. “Just because I made it look easy doesn’t mean that it was, and you don’t work hard and become a Hall of Famer without working day in and day out. I want to thank my family and friends, the fans, the Reds, the White Sox and Mariners for making this kid’s dream come true.’’

And with that, at the suggestion of fellow Hall of Famer Frank Thomas, Griffey took a Hall of Fame baseball cap and put it on his head backward: the way he used to wear his cap when he was the “Kid.” The crowd, a mix of mostly Mariners and Mets fans, went nuts, and it was a fitting end on a day when the start of the players’ careers was just as important as the end.