Joe Bob Briggs, the longtime champion of outlaw cinema, will visit Central New York this weekend as his “How Rednecks Saved Hollywood” tour makes a pit stop at Armory Square’s Museum of Science and Technology (MOST), 500 S. Franklin St. The venue’s Bristol Omnitheater will host Briggs on Saturday, May 11, 7:30 p.m. Tickets are $20; visit afterdarkpresents.com for information.

For the uninitiated, Briggs is the puckish persona of John Bloom, who invented the cowboy-hatted drive-in movie critic in 1982 for the Dallas Times Herald. Readers immediately embraced the tongue-in-cheek Briggs column, which praised the often sleazy virtues of B-movies that featured high body counts, copious amounts of nakedness and amateurish performances.

But Briggs’ career at the newspaper was derailed when his April 12, 1985, column parodied the “We Are the World” song about world hunger, which included the opening lyrics, “We are the weird/ We are the starving/ We are the scum of the filthy Earth/ So let`s start scarfin.” Briggs’ weekly column, which ran in 57 papers, was canceled by his syndicator, although another distributor quickly snapped up his quirky musings. Meanwhile, Briggs scored long-running TV gigs as the late-night host of demented flicks for The Movie Channel (1986 to 1996) and TNT (1996 to 2000).

Briggs displays an easy-going enthusiasm during his speaking engagements, and he obviously knows — and adores — his subject matter. At the MOST, Briggs will take on the joys of hicksploitation cinema, with emphases on good ole boys, sassy ladies, demolition derbies and all things Burt Reynolds. This is how previous venues have publicized the event:

“Spend a fast-and-furious two hours with America’s drive-in movie critic as he uses over 200 clips and stills to review the history of rednecks in America as told through the classics of both grindhouse and mainstream movies.

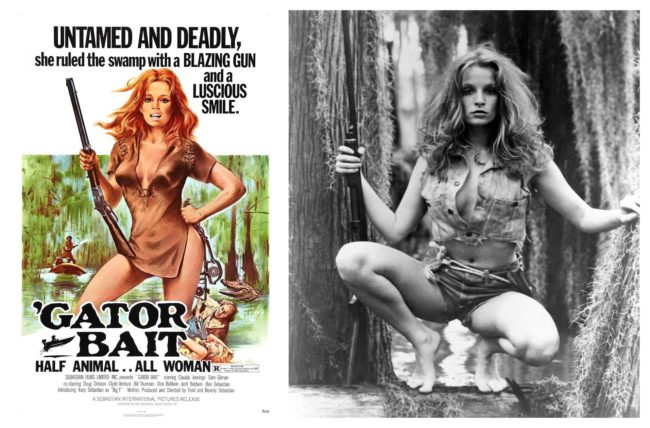

“You will learn: The identity of the first redneck in history. The precise date the first redneck arrived in America. The most sacred redneck cinematic moments. How Thunder Road, the Whiskey Rebellion, the tight cutoffs worn by Claudia Jennings in Gator Bait, illegal Coors beer, and the Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash combined to inspire the greatest movie in the history of the world. Why the redneck is the scariest monster in all of film history, with visual evidence. The existential difference between Forrest Gump and Sling Blade. The reason God loves rednecks.

“And dozens of other historical facts that you didn’t realize you needed until Joe Bob deposited them in the rear lobe of your brain.”

Before Briggs wings his way to the MOST, he gave the Syracuse New Times some insights about the redneck genre, snacks at the ozoners and one of the most influential directors in drive-in history.

The Black River Drive-In, circa 2012. (Michael Davis/Syracuse New Times)

Your first drive-in movie experience: When, where and what was playing?

I would have been a 4-year-old in the back seat of my parents’ car at the Red Raider Drive-In in Lubbock, Texas. We lived in a little town in the Panhandle called Springlake. Nothing there but an elementary school and a high school where my parents taught the cattle ranch kids who were bused in from all over Lamb County every morning.

On Friday nights they took me to the football games (Go Wolverines!) and on Saturday nights we made the 60-mile drive over farm-to-market roads, ending up at a two-screener that held about a thousand cars. I don’t remember what was playing but, typical of the period, it would have been a cheap western.

The 1970s seemed to be the redneck heyday in cinema. Even glossy, big-budget mainstream movies were not safe: Two successive James Bond adventures, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun, featured character actor Clifton James as Southern-fried Sheriff J.W. Pepper. Was it inevitable that redneck characters would take over Hollywood?

Redneck characters never took over Hollywood. Hollywood is too liberal for that. But since the most avid moviegoers in the country are rednecks — with more movie theaters per capita in the South than any other region —Hollywood always had to deal with it. Movie executives have always been embarrassed by redneck movies, even the ones that make hundreds of millions of dollars, like Disney’s Ernest franchise in the 1990s.

Can you explain the phenomenal successes of Poor White Trash (released as the box-office lemon Bayou in 1957, then recut in 1961 and reissued repeatedly throughout the 1980s) and Thunder Road, two movies that have likely wound through more drive-in projectors than anything else? Even Thunder Road star Robert Mitchum admitted in 1972 that his 1958 movie had never been reissued because it was never out of circulation.

Both movies became popular during the period when a beloved B-movie could sometimes play for decades as a second feature, especially at drive-ins. Thunder Road cashed in on the outlaw reputation of Robert Mitchum and the sad but true story of a moonshiner who crashed his car and died on Kingston Pike in Knoxville after being roadblocked by 200 federal agents. In that part of the country, running whiskey could never be a crime, so it was a powerful folk legend about a whiskey martyr.

Poor White Trash was set in the exotic swamps of southern Louisiana, where oversexed girls grow up fast. So these two movies represent the two major B-movie food groups: sex and violence. Or, for those who are not quite so judgmental, romance and adventure.

Have you ever consumed moonshine?

In a Mason jar, no less.

You had a smallish role in director Martin Scorsese’s Casino (1995). Did you get to discuss Scorsese’s redneck-flavored epic Boxcar Bertha (1972)?

Yes. One of the interesting things about Scorsese is that his crews know him so well that there are long periods where lights and cameras and tracks are being set up and he has nothing to do: He’s the only guy not occupied by the preparations. And he loves to talk.

So, yes, we talked about Boxcar Bertha and what would have been his first movie, The Honeymoon Killers (1970), except that he was fired after one week of shooting. Boxcar Bertha was shot in Arkansas, and Scorsese did extensive storyboards so that whenever the producer showed up (and the producer was Roger Corman), he could prove he knew what he was doing. He was in fear of being fired again since, after The Honeymoon Killers, he didn’t work for three years.

A number of drive-ins nationwide had to close their gates because they lacked the money (roughly $75,000) to convert from 35mm prints to digital projectors. Yet your old newsletter would often declare “Victory Over Communism” as you would celebrate an ozoner that was still in operation. Do you attempt to squeeze in some time to visit local drive-ins whenever you are on speaking tours?

I’ll visit any drive-in any time. I’ve been reading articles about “the death of the drive-in” for 50 years — and it’s still not dead! In fact, there are new ones popping up from time to time, such as the Coyote Drive-In in the river bottoms of Fort Worth, and there are old ones that re-open after being dark for two or three decades.

The biggest threat to a drive-in is land value. If the area around the drive-in starts to be heavily developed, the land becomes too valuable to use as a drive-in and it eventually gets sold off as the site of a new Wal-Mart.

What’s your favorite drive-in concession stand food?

I’m a Dancing Hot Dog fan myself, but there was a drive-in tradition in West Texas I never saw anywhere else: frozen pickle juice. They sold it in little paper cups and you would chew on it like a snow cone.

Movies like the 1974 thriller-drama “‘Gator Bait” ruled redneck cinema.

You hosted a VHS franchise titled “The Sleaziest Movies in the History of the World,” with a sweeping B rating that denoted either breasts, blood or beasts, or combo platters of all three. How much fun did you have curating these lost gems?

I’m actually proud of that series because it was a re-release and rediscovery of all the films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, better known as the Godfather of Gore, who made the classic Blood Feast (1963), and Doris Wishman, the only female exploitation director at that time, who made Bad Girls Go to Hell (1965), Nude on the Moon (1961) and A Night to Dismember (1983). Both filmmakers were living in South Florida when I went searching for them, and both were astonished that anyone would want to watch their old films.

How many cowboy hats do you own?

Four. But I still can’t find one that gives me that perfect Dwight Yoakum crease.

You have stated that the 1979 T’n’A drive-in comedy Gas Pump Girls featured a record number of nekkid Ts. Really? All this and Bowery Boys favorite Huntz Hall, too?

They just don’t make ’em like that anymore, do they?

I’m guessing that director-stuntguy Hal Needham (Smokey and the Bandit, The Cannonball Run) could be your favorite king of redneck drive-in features. But there are many other drive-in directors who rule the roost. Who are some of your favorites?

I don’t really think anyone compares to Roger Corman: He’s the Orson Welles of the exploitation film. The Fast and the Furious series is based on his original movie from the 1950s. Little Shop of Horrors has been celebrated on stage and screen for almost 60 years. The Edgar Allan Poe movies he made in the early 1960s, most of them starring Vincent Price, are drive-in classics.

He’s directed or produced over 700 films and never lost money on any of them: That’s a man who knows his audience. That’s a man who knows how to keep it redneck.